Gov. Phil Scott’s plan to provide $1.5 million to help Vermonters buy electric cars didn’t make many headlines when it was announced in January. After all, the federal government has offered electric vehicle purchase incentives of up to $7,500 for a decade. Local utilities, including Green Mountain Power, the Burlington Electric Department and the Washington Electric Co-op, offer similar rebates to help make electric cars more affordable.

But in many environmental circles, Scott’s announcement triggered a powerful reaction — alarm.

The proposal struck clean power advocates as paltry compared to the effort needed to meet Vermont’s ambitious greenhouse gas emission and renewable energy targets. Those goals have become more difficult to reach because emissions have been on the rise despite years of effort to wrestle them below 1990 levels.

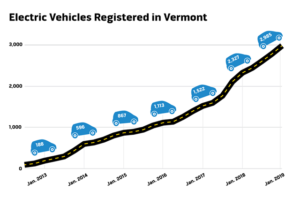

Last week, the House Transportation Committee urged House budget writers to add as much as $3 million to the electric vehicle incentive program. In its letter to the Appropriations Committee, the transportation panel noted that the state is well short of its goal of putting 50,000 electric vehicles on the road by 2025. As of January 1, only 2,985 electric vehicles were registered in Vermont. Plug-in hybrids are considered EVs, as are all-electric vehicles.

Last week, the House Transportation Committee urged House budget writers to add as much as $3 million to the electric vehicle incentive program. In its letter to the Appropriations Committee, the transportation panel noted that the state is well short of its goal of putting 50,000 electric vehicles on the road by 2025. As of January 1, only 2,985 electric vehicles were registered in Vermont. Plug-in hybrids are considered EVs, as are all-electric vehicles.

Rep. Mary Sullivan (D-Burlington), a member of the Transportation Committee, said the opportunity for a “transformative” change in the state’s transportation network has been reduced to a “piddly little program” that might put only a few hundred more EVs on the road.

“That’s not good enough,” Sullivan said.

Environmental advocates were similarly underwhelmed by Scott’s proposal.

“I think it’s a good, modest step forward that falls dramatically short in terms of the investment required to help Vermont transition to more efficient, cleaner electric vehicles,” said Johanna Miller, energy and climate program director for the Vermont Natural Resources Council.

The funding disagreement reflects growing anxiety among climate activists that Vermont, for all its progressive politics and environmental leadership, is falling further and further behind on its climate commitments. They argue that, while well intentioned, state programs just aren’t transforming energy use or reducing emissions nearly fast enough.

“We’ve been long on rhetoric and light on reality in terms of the thermal sector and the transportation sector in particular,” Miller said.

That became painfully apparent to her and others last summer when new data revealed that the state’s carbon emissions actually rose 10 percent during 2014 and 2015.

That June 2018 report, called the Vermont Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory Update, showed that emissions dropped 11 percent from a 2005 peak of 10.2 million metric tons of CO2 and equivalent gases to 9.1 million tons in 2013.

But when the economy picked up, so did emissions, rising by 4 percent in 2014 and another 6 percent in 2015, according to the report.

“The news from that report was startling and really disappointing,” Miller said.

The emissions bump pushed the state even further from its missed goal of cutting emissions 25 percent below 1990 levels by 2012. And it will be even more challenging to hit the next milestone of 50 percent below 1990 levels by 2028, said Jared Duval, executive director of Energy Action Network.

Duval said the governor’s incentive plan is lacking.

“It’s fair to say that anybody who looks at the numbers, who knows the data and what Vermont’s commitments are and where we stand, is past the point of being satisfied with first steps or symbolic actions,” Duval said.

The debate over how to boost EV ownership may seem odd to those who have considered Vermont a leader in the field. The Green Mountain State is fifth in the nation in EV ownership on a per capita basis, behind California, Hawaii, Washington and Oregon, according to David Roberts, coordinator of Drive Electric Vermont.

It’s also first in the nation in public EV charging stations per capita, with a network of more than 200 across the state.

But there are signs of headwinds for new EV sales in Vermont. After robust growth mid-decade, sales of new EVs fell from 806 in 2017 to 647 last year.

Changes in model offerings or incentives may have played a role. Few EV models are equipped with four-wheel drive, a requirement for many Vermonters. Other challenges include EVs’ diminished battery range in cold temperatures, higher upfront costs and the relative scarcity of public chargers — especially so-called Level 3 fast chargers — in rural areas.

Reducing transportation emissions may take far more effort and investment than previously envisioned. Last year, Duval’s group estimated that to meet the goal of the Paris Climate Agreement, the state would need to add 60,000 EVs by 2025. The group released revised estimates Monday that boosted that figure to 90,000 EVs.

Political promises are not translating to policies that will achieve the state’s goals, Duval said.

Electrification of Vermont’s nearly 600,000 passenger vehicles is just one piece of the state’s Comprehensive Energy Plan, which serves as the blueprint for how the state will meet its sustainability goals. The plan calls for 90 percent of the state’s energy to come from renewable sources by 2050.

Other initiatives include increasing the use of public transit, heating buildings with heat pumps and efficient woodstoves, weatherizing and insulating more homes, and relying more on renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar.

Because cars and trucks produce up to 53 percent of Vermont’s carbon emissions, however, advocates say the state can’t afford to miss any opportunity to increase the number of efficient and all-electric vehicles on the road.

The Scott administration is committed to boosting EV ownership, and the new incentive program is just the latest effort, said Peter Walke, deputy secretary of the Agency of Natural Resources.

He noted that the state held a sales tax holiday on EV purchases in 2017 and said the utilities’ incentives were no accident.

“They’re doing it because the state told them to do it,” Walke said.

Those programs have been effective but have also created a patchwork of incentives and rebates that vary widely depending on where people live, which can create confusion for consumers.

Scott’s proposed program would offer a uniform incentive program reaching every corner of the state and would specifically target low- to middle-income residents.

While the federal tax break is useful to those who have a large enough tax burden, it’s not helpful for low-income individuals, Walke said. Bringing down the sticker price is seen as the best way to help make an EV purchase pencil out for lower-income residents.

“Our goal is to make a dent in that lack of access,” he said.

As proposed, the incentives would provide up to $5,000 for low- and middle-income Vermonters who buy or lease new or used plug-in hybrids or all-electric vehicles. The lower a buyer’s income, the greater the incentive. Those earning between the state’s median income and 140 percent of it would receive $2,500 toward a vehicle. Those making less than the median income could qualify for up to $5,000.

At present, the incentive would apply to vehicles costing up to $35,000, but the threshold could increase to apply to popular new models such as the all-electric Chevrolet Bolt, which starts at around $37,000.

Depending on applicants’ incomes, the $1.5 million could help 300 to 600 new EVs hit the road over two years.

Walke said he understands the urgency advocates feel about speeding up the transition to EVs but argued that it’s common for a new program to start modestly and then, if demand materializes, to “turbocharge it,” if possible.

“If we get 300 low-income Vermonters into electric vehicles they didn’t have access to before, we wouldn’t declare that a victory?” he said.

In addition to encouraging residents to buy or lease electric vehicles, the governor’s budget also includes $500,000 for the purchase of more EVs for the state fleet and installation of new charging stations.

Of the state fleet’s 2,220 vehicles, just 27 are EVs — 25 plug-in hybrids and two all-electric vehicles, according to fleet manager Harmony Wilder. Many of the state vehicles are heavy-duty trucks with no electric alternatives, such as snowplows and four-wheel-drive vehicles.

The state hasn’t added more EVs until now because the cost of installing charging stations makes EVs more expensive than maintaining the existing gasoline fleet or reimbursing employees for mileage in their own vehicles, Wilder said.

The additional funds would allow perhaps 12 new EVs to be added to the fleet, as well as the installation of charging stations at several state facilities that don’t yet have them, she said.

It’s not clear where any additional funds might come from to boost the incentive program. Under the administration’s proposal, $1.5 million would come from a state legal settlement with Volkswagen over its diesel emissions fraud.

The Transportation Committee has suggested up to $3 million more could come from that fund and other expected settlements with Fiat Chrysler and Bosch — deals Attorney General T.J. Donovan announced in January.

The House Appropriations Committee is expected to take up the issue next week.

“There are millions of dollars in additional requests, so it’s a balancing act,” said Rep. Kitty Toll (D-Danville), who chairs the committee.

House Transportation chair Curt McCormack (D-Burlington) said it’s not just the budget that hangs in the balance, but the planet.

He cited last year’s United Nations study estimating that humanity has just 12 years left to curb emissions enough to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change. The state ought to be pumping “more like $20 million” into the program and showing bigger states it can be done, he said.

“I’m not sure everyone is realizing the urgency,” McCormack said. “We have to act more quickly than we usually do.”